- Home

- Gabrielle Korn

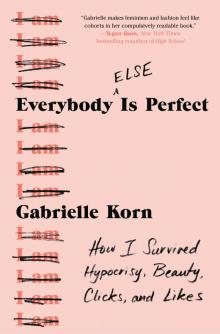

Everybody (Else) Is Perfect

Everybody (Else) Is Perfect Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For my sisters, literal and otherwise

Prologue

Dear Readers,

For two chaotically busy, gloriously productive, high-profile years, I was the US editor in chief of an international, independent publication called Nylon—a promotion I got when I was twenty-eight, younger than any Nylon editor in chief before me, and definitely the only lesbian who’d ever been at the top of the masthead. I was, in fact, younger and gayer than all the female EICs at competing publications in New York City, which was a point of pride for me but also made me an outsider. People like me were not supposed to get promotions like that.

What’s more, I was promoted on the same day the print magazine, which was in many ways beloved and iconic, folded. It was a terrifying task, but being put in a position of power meant that I could pour my idealism into something concrete: institutional change. I loved the brand but saw its flaws very clearly, and I was committed to building an editorial strategy that prioritized racial diversity, that welcomed all bodies to the table, and that didn’t limit the idea of coolness to a certain economic class.

Speaking of coolness: Growing up, I had been, in many ways, the kind of person for whom Nylon magazine was created, but I never felt like I was cool enough to read it. Like other magazines, it was so exclusive that it barely included anyone. As a teen in the early 2000s, I was an art kid who loved fashion but not in a popular-girl way, who self-identified as a music snob at fifteen, who dated skaters, who went to emo shows and played guitar in a punk band. Nylon was sold at Urban Outfitters, where I shopped; it partnered with Myspace, on which I spent my free time. It had always been in the background of my life. But as a queer woman, I also didn’t see myself reflected in its pages, or really, any glossy magazine pages at all; even before I had words for my deepest desires, I felt that there was something inherent that rendered me other.

Maybe because of that, when I was younger, working as a magazine editor didn’t even occur to me. I fluctuated between vague ambitions. Sometimes I wanted to be a painter or a photographer, other times a poet. But I also wanted to write articles, and as I tried to make a career around online journalism in my early twenties, the lifestyle publications were the ones that paid me. And as someone who cared a lot about my own physical appearance, I also turned out to be good at writing about aesthetics in a compelling way. I found myself pulled toward the vibrant, bustling world of New York City fashion media, as though it weren’t a choice but an inevitability.

In my early days as a beauty editor, I was confronted by how a women’s industry could be so obviously centered around, and controlled by, a straight, cisgender, white male gaze. I was astounded to watch my inbox fill every day with pitches from publicists about how to groom my body hair to please “my man”—I’d then watch as competing publications that had clearly gotten those same pitches would run stories using the same language. So, in turn, I began to churn out work about not shaving your body hair, among other things, and in general I became a very vocal, probably annoying, voice for change. What was the point, I asked myself, in working myself to the bone for big, fancy publications as a dyke if I wasn’t going to try to make the content accessible for other queer people?

Eventually I went to Nylon, where I was a digital editor for three years before my final promotion to the top spot, which meant the people in charge were finally starting to listen to alternate viewpoints. It was a huge win not just for me but for everyone like me who didn’t see themselves represented in mainstream media.

Behind the scenes, though, a very different story had unfolded.

I’d achieved something majorly shiny and glamorous, but along the way, it hadn’t been so pretty. At various times, I was underpaid, discriminated against, and sexually assaulted. And despite my fancy day jobs, in my personal life, I consistently behaved like a typical twentysomething: I was dating women who didn’t treat me well, I was sleeping with women I shouldn’t have, and I was struggling to figure out how to identify my own needs, which in turn made me a shitty person to be in any kind of relationship with. I smoked too much pot and didn’t get enough sleep. I alienated people who loved me with my inability to ask for help and my tendency to self-isolate.

I was also trying, and failing, and trying again, to recover from anorexia, a secret struggle that impacted every single aspect of my life. In contrast with my personal brand, the hypocrisy of my diagnosis wasn’t lost on me, and that was just one more reason for me to be filled with self-loathing. Once I had big, “important” jobs, I was more than happy to hide behind the busyness that came with them, rather than face my own demons.

I wanted so badly to show the world that an iconic fashion-based publication could become a beacon of thought leadership if you just let young women steer the ship. And we were very successful. I prioritized diversity within everything we made, and the brand evolved. Young readers called us “woke Nylon.” My junior editors called me “Mom.”

Eventually, I made a name for myself as a champion for inclusion. Work was still crazy, but by the end of my twenties, I was starting to get my emotional life together, falling in love with a woman who treated me with kindness and respect. I felt I knew myself. And then, in July 2019, two months after my thirtieth birthday, Nylon was suddenly acquired by a much larger company. I was caught completely off guard. I hadn’t realized how burnt-out I was until that moment. I felt like I had nothing left to give, and so I resigned.

I had thrown myself fully into the work of making women’s media safe for all kinds of bodies but had become almost disembodied in the process. I could power through exhaustion and starvation and high heels that tore up my feet, and justify it with how important the work would be to other people.

I’d been led to believe that notoriety is the ultimate aspiration, but the truth of the matter was I had been running a company as though it were mine when I didn’t own a single piece of it. I had made positive change, but when you strip all the pretense away—the things our culture says make you an empowered woman—what’s left? Who are we, as contemporary feminists, without capitalism?

I realized that without my fancy job title, I didn’t know how to describe myself. And really, the question for all of us is this: As a new generation of women, how do we recognize ourselves and each other without the pressure to be perfect—however that’s currently being defined?

I learned the hard way that professional success is not a good indicator of well-being. And I believe that is a deeply relatable phenomenon, though it’s usually spoken in whispers, especially for women. So when I quit my big, fancy job, after spending a few weeks moping, I got to work. But it was a new kind of work, and the first step was returning to my own body. The second was remembering what it felt like to have ownership of my time. The third was deciding what to do with it.

I also, immediately, had a book to finish—you’re holding it.

In the yearlong period between pitching the idea and finishing the manuscript, my life had been turned upside down. And I came out the other side stronger, and more self-aware, and with a clearer idea of what I needed. Suddenly, I had a much bigger story to tell.

This is a book about what happens when you put your own well-being on hold to achieve a version of success that you t

hink you’re supposed to want, and how I finally was able to see—and then escape—the confines of perfection. I hope you enjoy the ride.

Gabrielle

1 The Beautiful Flaw

In early 2013, a few months before I turned twenty-four, I landed a job as a production assistant in the beauty department of a rapidly growing digital media company for women called Refinery29. The job itself (building posts in the back end and photo research, mostly) wasn’t exactly a dream, but the company was: a newly notable fashion site defined by superiorly cool taste, it was trying to become the world’s destination for style. I didn’t know too much about fashion, but I loved clothes and makeup. I’d been writing for Autostraddle—an online magazine for queer women—for a little over a year and had gotten lucky: the woman I sent my resume to was familiar with the website and had been interested in improving the diversity of the beauty department. As a lesbian, I was a diverse hire. It was also good timing—a few months after I started, the company strategy shifted and our department went from being responsible for five stories a day to around twenty. My editors, grateful for my youthful enthusiasm, quickly gave me more responsibilities, and eventually I was writing stories all day on hair, makeup, skin care, and nails.

The intense increase in article production was helmed by a hardworking, talented editorial team that was willing to be experimental at a time when the competition was playing it safe, and it worked. Like, really worked. Soon there was a site-wide traffic boom so enormous it seemed like every week we were champagne-toasting a new milestone. We sailed past ten million unique readers per month and continued to climb. The offices moved from one large room in the East Village to two entire floors of a skyscraper in the Financial District. A huge flat-screen TV was mounted on the wall in the editorial department so that Chartbeat, a dashboard that shows you in real time how many people are on your site, was always visible.

The brand gained name recognition in the industry, and the writers were getting noticed, too, literally: I was regularly stopped on the street by young women who recognized me from my byline photo and DIY videos. It was thrilling; there was a large part of me that always doubted I could become a successful writer, and the attention was flattering and addictive. Beauty brands started flying me around the world—I went to Singapore to cover a skin-care brand, Milan for the launch of Gucci makeup, Nashville when Carrie Underwood became a makeup spokesperson, Paris for a new hair dye innovation. Even though I was still an assistant, telling people where I worked would elicit a breathless “Oh!”

Then, of course, the numbers plateaued. We scrambled, working all hours of the night to be the first to cover a Kardashian hair change or announce the launch of a new Urban Decay Naked Palette. It wasn’t working. Even though we were maintaining, not losing traffic, a sense of defeat hung in the air. Chartbeat, which had so recently set the room aglow with success, now loomed above us, a constant reminder of how we’d slowed.

Digital media, especially at that time, was an endless roller coaster dictated by clicks, and it was difficult to tell from one day to the next which stories would take off and which would die upon publication. This was the beginning of social media’s reign of terror over the industry. Suddenly the way a link was posted on Facebook, and when, would be the difference in tens of thousands of visits. But it didn’t seem like an institutional problem yet—instead of criticizing the system, we pointed fingers at each other, and ourselves. It wasn’t uncommon to try to find a private place to cry, like a stairwell, only to find someone already there doing the same thing. There was one day when I wrote ten news posts in a row; by evening, my eyes felt like they were bleeding. There were many people who were writing even more than me. In hindsight, I have no idea how we did it.

In this liminal space without strategy, there was a unique opportunity: we were encouraged to try just about anything. No pitch was too crazy. First person seemed to work well for our competitors (it was, after all, the middle of the first-person essay boom, also commonly referred to online as the first-person industrial complex), so we all started digging deep into our own psyches. Eventually I turned out a story called “People Have a Lot of Feelings about You Not Shaving.” By “you,” I meant me: I wrote about my high school guidance counselor telling me not to apply to a small liberal arts college in western Massachusetts because it was filled with “hairy lesbians,” and how though I didn’t apply, I grew up to be one anyway. I talked about the reactions I got when people noticed my various body hair—hostile stares on the subway, an uncomfortable check-in with a former boss about what’s appropriate for an office setting. Strangers told me I looked like a man. Well-meaning acquaintances often asked to touch it.

This was around the time that “no-makeup makeup” was becoming popular. Thanks to the Beyoncé song, people started tagging their selfies #wokeuplikethis to promote natural beauty and also, probably, to feel morally superior about it. In my self-righteous twenty-four-year-old words I proclaimed that there was a difference between natural beauty and radical beauty—that the former is a privilege for those who fit the standard, and the latter is about reclaiming the concept of beauty for identities that are usually excluded from it. The point was that it’s possible to make a political statement with your grooming habits. Basically I was writing about queer signifiers for what was, at the time, a mainstream fashion website. It was something I felt particularly strongly about because I was extremely conflicted about launching a career in an industry I’d always felt excluded from: I was holding on tight to my identity, determined to not be erased. In the essay, I talked about how important it was for me to be seen, and how my long body hair juxtaposed with the short hair on my head gave me the visibility and validation I craved—which was as true in my new workplace as it had been in college. It went viral.

Soon everything I wrote was about alternative beauty, calling out the ways in which the industry was failing women by putting us in boxes. I felt like a feminist infiltrator, taking down the system from within. I wasn’t alone: writers in different verticals experienced a similar trajectory. Those of us willing to expose our deepest selves, to use fashion and beauty as a window to talk about more serious issues, were rewarded with traffic and respect. It was “it happened to me” for millennials: the format made viral by xoJane combined with a second-wave personal-is-political ideology. Eventually, there was a mandate across editorial that everyone needed to start writing personal essays, and gradually our traffic was back up. I quickly learned that the up-and-down nature of web traffic was the norm, not just there but across the industry.

Because my most popular writing tended to be about redefining beauty standards, I was eventually asked to write a story that was to be called “My Beautiful Flaw.” The idea, as explained to me, was to create an originally photographed slideshow and accompanying interviews of maybe seven to ten women, all of whom should have what other people might call a flaw but from which they derived a sense of empowerment or specialness. “Like someone with two different-colored eyes,” the assigning editor told me.

Getting such a major assignment at my level was a huge opportunity, but the task of casting for the story filled me with anxiety. Who was I to decide what constituted a flaw? And many of the women I initially reached out to were so offended by the question (“You think my hair/nose/skin is a flaw?” was, not surprisingly, the usual response) that I had to change the wording entirely, even though I knew the final headline would probably have to be what the editor originally wanted.

Then there was an added layer of trouble: I easily found dozens of women with some sort of standout feature, like a very visible scar, or prematurely gray hair, or some asymmetry, all of whom were roundly rejected. It quickly became clear that every woman featured, while being lauded for her “flaw,” still had to be conventionally attractive and trendy. “Can’t you just find, like, a model with one blue eye and one green eye?” was the feedback. Eventually I put an ad on Craigslist and was flooded with responses. I contacted agencies

; I had all my friends reach out to all their friends. I started to become familiar with what would get rejected ahead of time—no matter how remarkable someone’s scar was, if she wasn’t also classically pretty and hipster cool, it was a no. I was overwhelmed with both guilt and powerlessness.

The whole thing started to feel like a round peg in a square hole. What’s the point of celebrating differences if you’re going to put parameters around just how different they’re allowed to be? The implicit message was, It’s okay to have something weird about you, as long as, overall, you’re easy on the eyes. I started to realize that this probably applied to my own editorial success. Sure, I had short pink hair and fuzzy calves, but I was also white, skinny, and young, and my clothes were cute. My aesthetic differences were just quirks.

Eventually, after I left, the company would pivot their content to champion both racial and size diversity—though internally, it would struggle for a long time to develop a work culture that matched the new mission of the editorial. But in the era of “My Beautiful Flaw,” most mainstream fashion publications, digital or print, were still predominantly filled with images of thin white women. Despite my queerness, I was just another one of them. I understood that as a white Jewish lesbian, the parts of my identity that might marginalize me were largely invisible; I was benefiting from the system while being tokenized by it.

In the end it took six months to get just three women approved for the story, and we decided to cap it at that, before I lost my mind. I convinced my editors to let me change the headline to “Why Beauty Isn’t about Being Perfect,” which was still mildly offensive to the women featured, but less potentially devastating. Of the three, one was a runway model with albinism, one was an activist with vitiligo, and one was a writer with a delicate scar down the middle of her face. All of them were beautiful. And despite the headline, they were all pretty much perfect, too.

Everybody (Else) Is Perfect

Everybody (Else) Is Perfect